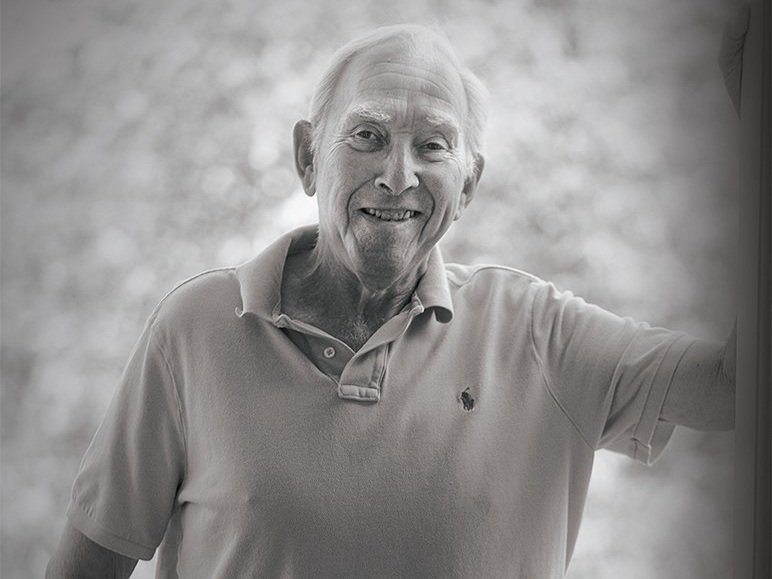

Talking History with Jack Topchik

by Scott Grove

In 1971, military analyst Daniel Ellsberg leaked a top-secret report, known as the Pentagon Papers, that documented the impossibility of winning the Vietnam War. Frederick resident Jack Topchik worked as an editor at The New York Times, the newspaper that was the first to publish the report. He shares his memories of the event that led to America’s long-awaited withdrawal from Vietnam and played an important role in the preservation of the free press. Ellsberg died in June of this year at age 92.

Scott: How did you get a job at The New York Times immediately after college? That’s a journalist’s dream come true, one that typically happens only after many years of work experience.

Jack: A few weeks after graduating from the University of Tennessee in 1967, I returned home to New Jersey. One day I saw an advertisement in The Times promoting its classified section that read, “I got my job through The New York Times.” The next day I decided to meet with their recruiting director. I’d majored in journalism and brought a folder of my writing. She said that The Times always had enough reporters but never enough editors. She said that if I never pressed them to be a reporter then they had a job for me. I was to edit news for The New York Times News Service, which selected and transmitted news articles to more than 500 newspapers nationally and globally. The Times was a demanding boss. Rule #1 was objectivity, regardless of an editor’s political, social and religious views. Rule #2 was an obsession with accuracy. Every fact, every name, every spelling, every date had to be correct. Objectivity and accuracy remain the hallmarks of The Times.

Scott: In 1971, four years into your career, The Times got access to the Pentagon Papers. Tell us about that.

Jack: Daniel Ellsberg was an American political activist, economist and military analyst who had become disenchanted with the way the U.S. government was reporting on what was happening in Vietnam. It was apparent to Ellsberg in his writings that our efforts in Vietnam were failing. While employed by the Rand Corp. (a research organization), he precipitated a national firestorm and First Amendment cause célèbre after he released a top-secret study exposing government decision-making in relation to U.S. involvement in Vietnam as far back as the 1940s. Ellsberg released copies of the study to Times reporter Neil Sheehan, who then turned it over to the executive officers at the paper. News of the Pentagon Papers circulated through the newsroom at The Times, but few newsroom personnel knew what was soon about to happen. The evening before the first of the daily installments of the study was published, the newspaper announced that the bulk of the next day’s Times would be dedicated to the Pentagon Papers and that several articles that were planned for the paper would be placed on hold to make room for the first stories. Max Frankel, The Times executive editor who received the Papers from Sheehan, later wrote in his book, The Times of My Life and My Life with The Times, that Sheehan never revealed how, or from whom, he received the 47 volumes that made up the Pentagon Papers.

Scott: Do you remember the staff’s reaction to all of this?

Jack: Even for those of us in the newsroom who were relatively new, it was obvious that publication of the report was going to be a major undertaking. There were whisperings that the government was furious over the leaking of the Papers and that lawsuits challenging the Times’ right to publish the report were imminent.

Scott: Was management all on board with the decision to publish?

Jack: Frankel’s book reveals the divisions among the top executives about the viability of publishing a stolen government report while the United States was still at war in Vietnam. After the first installments were released to the public, the Department of Justice obtained an injunction, which halted publication of the Papers in both The Times and The Washington Post, which had also begun publishing the report.

Scott: What was the mood among staff at the paper?

Jack: Before the injunction, the feeling in the newsroom was one of pride for The Times’ willingness to take on the federal government. After the injunction, the mood turned to anger. There was a sense that the government reaction was overkill and threatened the First Amendment’s guarantee of a free press. Within a few weeks, the Supreme Court dissolved the restraining order and publication of the report resumed. Two years later, in 1973, the Watergate scandal led to further disappointment within the nation as to the proper role of government and to the loss of faith in traditional instititions. Not much appears to have changed in the 21st century.

Scott: How did you feel about having worked for one of the world’s most recognized and popularly read newspapers?

Jack: Working for The New York Times fulfilled a lifelong dream for me, having known since age 9 that I wanted to work in journalism. Throughout my 40-year career at The Times I was always excited to walk in the front door.

Jack Topchik and his wife, Carol, moved to Frederick County from Westchester County, N.Y., in 2009 and are enjoying life in Downtown Frederick. Scott Grove is the owner of Grove Public Relations, LLC, an advertising and marketing firm. A former reporter and lifelong student of history, his work also includes interpretive planning and design for museums and historic sites. Grove is the co-creator of the Frederick Maryland Walking Tour mobile app. For more info, visit itourfrederick.com or grovepr.com.