Class Dismissed

Brown v. Board of Education Changed America, But Painful Memories Remain

By Kate Poindexter

Photography By Turner Photography Studio

Joy Hall Onley clearly remembers her first day at Frederick High School, just not very fondly.

Four years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling integrated public schools across the nation, Onley and three friends from the all-Black Lincoln School on Madison Street walked the few blocks west to the previously all-White Frederick High. It was September of 1958.

“All we saw were older people, parents,” Onley recalls. “They yelled at us and called us names. I wasn’t hit with anything, but on the steps, there was a little shoving and tight quarters. We didn’t see a policeman; we didn’t have any protection.”

She was 15 years old. “At that age, verbal assault does a lot,” she says.

Prior to that day, Onley and her peers didn’t know much about the Supreme Court decision that ultimately changed their lives. They read, saw photos and news footage, and heard there had been some trouble in the South. Their parents were already proud of them for their academic success and character, but integration tempted them with the chance to further their education with better textbooks and newer equipment, and to open up their minds and their world. Their teachers at Lincoln encouraged them to make their own decision whether to change schools. When their principal offered them the chance to be the first Lincoln students to transfer to Frederick, they said yes.

Brown v. Board of Education transformed the public schools by legally ending the so-called “separate but equal” educational system that kept students segregated. Nearly 70 years later, Onley and three of her schoolmates recall how Frederick County’s adoption of the high court decision set them on a course that disrupted their thinking about race, education and society.

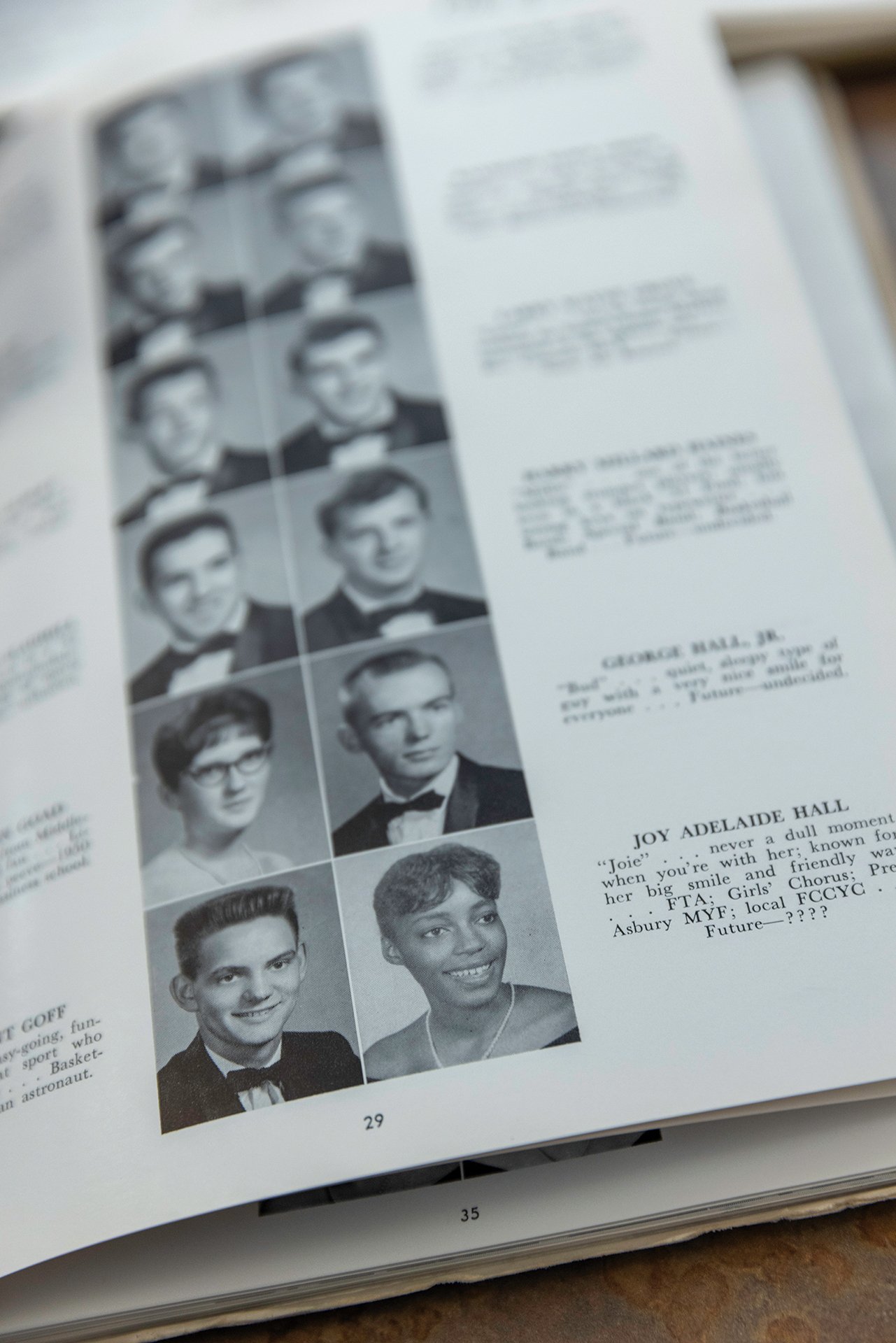

She and 12 other African American students from K-through-12 Lincoln were selected as the first Black students to attend Frederick High. One student went back to Lincoln after the first day at Frederick, Onley recalls, but the others pressed on. Now in their 80s, Onley, Ruth Ann Bowie Heath, Alphonso Lee and Patricia Ann Hill Gaither still keep in touch and occasionally talk about their high school days.

THE PLAN

When Brown v. Board of Education was handed down on May 7, 1954, it profoundly affected the country at a time when segregation extended far beyond schools, to theaters, hotels and many other public accommodations. Frederick’s Baker Park, which neighbors Frederick High, was open only to White residents.

Reaction to the ruling came in the form of protests and demonstrations that made headlines as many Black children approached schoolhouse doors in the South only to be blocked and turned away. There are famous photos of police escorts for African American children and adults shouting racial epithets. Little Rock, Ark., became infamous for the mistreatment of children trying to enter Little Rock Central High School in 1957. The Little Rock Nine gained entrance to the school only after President Dwight D. Eisenhower intervened.

Frederick’s response to the court ruling on integration was more controlled. On June 5, 1955, the Board of Education issued a proclamation that read in part: “The Frederick County Board of Education accepts the decision of the Supreme Court as the law of the land and expects to cooperate with the decision by desegregating its schools. In the opinion of the Board a lack of building facilities in several areas of the county does not make it feasible to begin desegregation in the county schools until the fall of 1956. The Board is now engaged in a building program and has three buildings in the planning stage which are expected to be finished by September 1956, or shortly thereafter. Their completion will make it feasible to begin desegregation on the junior and senior high school level.”

Joy Hall Onley

The school board then created a Lay Advisory Board consisting of parents, educators and community leaders whose mission was to help the public accept integration. The panel put together a five-part plan with these broad principles:

• There should be integration in every area, but not necessarily in every school, because of physical limitations.

• There should be full integration as soon as facilities are available.

• Children should be offered the option of attending the integrated school in their area or the school they are attending at present.

• Students who desire courses not offered at their own high school, but are given in another high school, may petition the Board of Education for a transfer.

• Transportation should be integrated this fall (1956).

The school board executed the school integration plan from 1956 through 1963.

On paper, at least, it seemed straightforward. The reality proved to be bumpier, at least for many Black students moving into new schools.

COLD RECEPTION

Onley and her friends from Lincoln noticed on their first day at Frederick High that they did not share any classes together, so they were navigating the hallways on their own. The first weeks she spent trying to find her way through the large building, sometimes asking other students for directions to a specific classroom and being sent on a wild goose chase. In at least one classroom she was assigned a seat up front, which made her a target for paper and paperclips being thrown at her from behind. A couple of teachers showed warmth to her, she says, but others were cold, even dismissive of her concerns.

Ruth Ann Bowie Heath was also 15 in 1958. She had all the jitters that came with going to a new school, but also became nervous about keeping up academically with her new classmates. She was chosen to go to Frederick High because she was a good student, but she found that she was falling behind. At Lincoln, she earned As and Bs. Initially at Frederick High, she was taking home Cs and Ds. She thought something was amiss.

“The teachers were very hard on us,” she says. “I really felt the grading was harsh by design. That’s just how I felt. I’m saying this because when I eventually went to college to study accounting, I got good grades.”

Heath says that although the environment at Frederick High was less than friendly, she is proud that she applied herself to her studies. She was able to go on to college and work for the federal government at Andrews Air Force Base. “I’m proud of what we did and that I was chosen,” she says. “The only regret I have is that I didn’t have a normal high school social life. I didn’t make close friends. I wasn’t invited or accepted into clubs at school. It’s like you were there, but you were avoided. Nobody was overly friendly.”

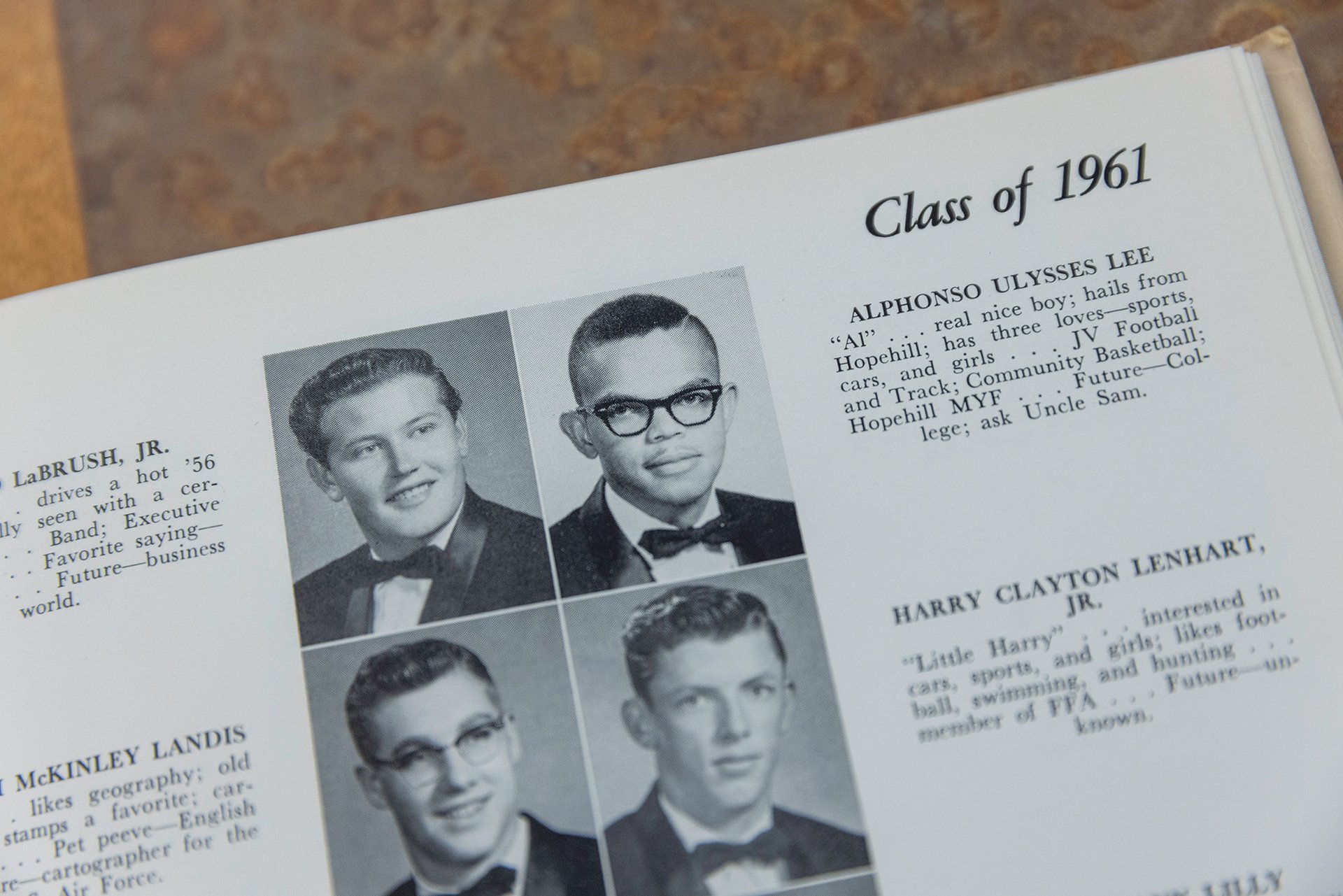

“We didn’t know what to expect,” says Alphonso Lee. “So, we just accepted what came along. There was name-calling, not directly at you, but you could hear what was going on.” Like Heath, Lee appreciated the new textbooks, not the

hand-me-down books he had become accustomed to at Lincoln. He worked hard in school and even made friends with some White students along the way, although some friendships were governed by the clock.

“Some of them were your friends when you were in school. But after 3:30 in the afternoon, they didn’t know you,” he says. Lee says his work ethic and his upbringing helped him get along with others and graduate. “I was raised to respect everybody, regardless of race,” he says.

After high school he joined the Air Force, worked at the National Institutes for Health for 26 years, and at age 81 still works at his own cleaning business in Frederick. He offers advice to young people. “Do the best you can in school. Everybody can’t go to college. Do good with what you have at your disposal.”

WRONG DIPLOMA

Patricia Ann Hill Gaither was the first African American female to graduate from Frederick High in 1960. She started there as a junior and despite working on the rigorous academic, college-bound track since 1958, she received a general diploma. “They deflated my balloon,” she says. It was not until 2023 that Gaither was given her rightfully earned academic diploma.

Gaither says choosing to attend Frederick High robbed her of the tight-knit community she knew at Lincoln. She did not find much encouragement or friendship at Frederick; some of her experiences with students and faculty were unpleasant and others were downright confusing. She says a history teacher once pulled her aside and asked if she would mind studying an upcoming lesson on African American (Negro) history. “I didn’t understand why he would ask me that. I just told him I didn’t have a problem. I was there to learn.”

Patricia Ann Hill Gaither

The frustration she experienced even spilled over into her 10-year high school reunion. A White classmate encouraged her to attend the reunion but rebuffed her when Gaither and her husband tried to pull up a chair at a table at the event. She was told those seats were taken.

After graduation, Gaither was employed by Dr. Vivian Thompson, an African American dentist, and then went to work for Farmers & Mechanics Bank. She also worked at Carmack Jay’s and Weis supermarkets. Now she looks back on her high school years and still considers race and its place in the classroom and the world. She even wonders about the utility of the terms “Black” and “White.”

“If you look at me, I’m brown,” she says. “Why does the world want to call me black?”

PERSPECTIVE

Joy Hall Onley says she is proud of her accomplishments at Frederick High and beyond. She graduated from Frederick Community College and enjoyed a long career at Frederick County National Bank. She has written two books and is considering another one about her high school experience. It’s still difficult for her to go back over the trauma of being a teenage girl caught up in the circumstances of the time.

Would the four friends do it all over again? Each says yes. They agree that what they did was important and opened doors for others. While they learned hard lessons about life, they hope their classmates and those that came after them learned lessons, too. They hope people continue to learn about civility, dignity and equality.

Alphonso Lee laments young people still need to navigate racism. “Things are more sophisticated,” he says. “Today, whites still let you know to some extent that you are black, no matter what you do.”

Ruth Ann Bowie Heath says she talked to her own children about navigating school when they were young. She admits the episodes of violence and intolerance she now hears about in schools concern her. “With antisemitism and other stuff, where are the parents? I think the parents, not just the schools, need to advise kids today,” she says.

Joy Hall Onley says even after all she has been through, she maintains hope for the future. She advises young people: “Go as far as you can. Don’t ever accept no!”

Patricia Ann Hill Gaither’s advice is simple. “Don’t give up. Hang in there. Keep on praying.”